"Students of the history of ideas are often preoccupied exclusively with the tracing of connections between ideas. This approach is too narrow and does not allow for the proper appreciation of some of the most influential men. A good deal of history, and of the history of ideas, too, consists in the untiring efforts of posterity to do justice to some individuum ineffabile (to use a phrase of Goethe’s). Socrates and Jesus, Napoleon and Lincoln are cases in point. So is Goethe."

Walter Kaufmann: From Shakespeare to Existentialism

This short opening passage in Kaufmann's essay on Goethe and the History of Ideas is profoundly significant in further advancing our enquiry into the nature of the problem of traditional historiology in India. Indians are very often quick to trace various historical connections from Europe to India; they may do this by pointing to the "Arabic numerals", the Number Zero (śūnya), to early calculations of pi (π), or various forms of astronomical and mathematical genius, and so forth. This intellectual "heritage" of Indian literary culture remains in some sense valuable to historians today, but does little to enhance the basic existential condition of Indians living in an economically depressed, densely populated state.

If the history of ideas—or, if we can say, in the same breath, the idea of history—is to break free from a mere fossil record of past events, and is rather to become a living practice of enhancing the dignity of existence, then it must be admitted that Indian literature needs to be investigated with the partial aim of breaking away from the ossification of thought—to wit, from the uncritical thoughtlessness of super-stitions. Such a radical or critical take on Indian literature has already been initiated by the Western Academy and is well underway yet, to my reading, it has stalled out, or rather, has advanced in such a way that the meaning of the most ancient of these works has remained deeply obscured for those whose significance it intersects closest with (i.e., "Hindus"), and thus, the history of Indian literature—again, meaning in the same breath, the literature of Indian history— itself has gotten, to some extent, lost in the rhetoric of skeptical reconstructive efforts which fail to take the pursuit of the meaning of these texts with adequate sensitivity to the worldview related therein. This can only result in the further perpetuation—and indeed, ossification—of misunderstanding.

If the history of ideas—or, if we can say, in the same breath, the idea of history—is to break free from a mere fossil record of past events, and is rather to become a living practice of enhancing the dignity of existence, then it must be admitted that Indian literature needs to be investigated with the partial aim of breaking away from the ossification of thought—to wit, from the uncritical thoughtlessness of super-stitions. Such a radical or critical take on Indian literature has already been initiated by the Western Academy and is well underway yet, to my reading, it has stalled out, or rather, has advanced in such a way that the meaning of the most ancient of these works has remained deeply obscured for those whose significance it intersects closest with (i.e., "Hindus"), and thus, the history of Indian literature—again, meaning in the same breath, the literature of Indian history— itself has gotten, to some extent, lost in the rhetoric of skeptical reconstructive efforts which fail to take the pursuit of the meaning of these texts with adequate sensitivity to the worldview related therein. This can only result in the further perpetuation—and indeed, ossification—of misunderstanding.

How is it that Indian literature has lost its historical (or should we say, aitihāsika) voice? Why does the Western academy still for the most part disregard all classical Sanskrit historiography as specious and unreliable in its own right (cf., Pollack, Sheldon. Mīmāṁsā and the Problem of History in India)? More importantly, in our Postcolonial phase of Indological studies, can this situation finally be rectified? Certainly there are elements in the classical historiography of South Asia which present complications, elements of mysticism so seamlessly blended in with terrestrial events that one finds it naturally quite difficult to tell where one starts, and where the other ends. But if we were to have, at the very least, a consistent sense of the domains of being to which we could ascribe our narrative structures, or rather, if we might take the ontology of Indian literature as critical post-sign, pointing us to these domains, then we are well on our way toward disclosing the presence of data which indicate a discernible concrete sensibility in the classical works. Securing the elements of these domains are not light work, but depart from the enigmatic condition which generated the existential concerns to compose these ritual works in the first place.

We are told that Vedic literature is, at its core, sacrificial, meaning, putatively—a concern with ritual activities bent on magically giving rise to desired fruits, or karma-phala. The early parts of the Vedic canon are for this reason often described as karma-kaṇḍa, or the "division of action", ritual action, to be precise. Yet the bases of the engine of sacrifice is to a large extent not given enough attention—at least, insofar as these bases constitute the original metaphysical threads upon which the whole efficacy of the ritual was conceived to rely. Brian K. Smith, In his work, Reflections on Resemblance, Ritual, and Religion, has spoken of jāmi ("family relation"; cf., Wittgensteinian notions of "family resemblance") as a critical thread for ritual efficacy, and certainly, this element does play into the larger picture of Vedic ritual. Yet, there are other components whose hitherto underestimated contributions have prevented scholars of Vedic materials from clarifying such works as the Brāhmaṇa texts. Even Michael Witzel, one of the world's premier Indologists, admits to a number of obscure passages for which he is unable to find a completely sensible meaning. Witzel provides us one such example from the Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa:

'The horse is connected with Prajāpati'; 'The horse is connected with the waters'; 'The horse (aśva) has 'tear' (aśru) as its secret name'."

'The horse is connected with Prajāpati'; 'The horse is connected with the waters'; 'The horse (aśva) has 'tear' (aśru) as its secret name'."

Witzel is perplexed by the meaning of these "connections", as he states:

"When coming across the sentence 'The horse is connected with the waters', this seems to be an unintelligible statement as many of the equations referred to above. As far as I can see, no relevant noem, no important concept of our encyclopedic knowledge connects 'horse' with 'water'." Now, in essence, I do think that he has hit upon the right sensibility, as when he quotes: " "The gods love the hidden, the non-apparent" (parokṣapriyā hi devāḥ)" Yet I think he goes awry when he then considers this hiddenness to consist merely in the similarity of sounds. "aśva 'horse' is aśru 'tear' because they share, as in the earlier example of dakṣiṇā = dakṣiṇaḥ, a similarity in sound."

Of course, it may be that this "symphony" matters, in the sense of jāmi, i.e., the sounds being neither identical nor entirely different, but just "similar". Yet there are other elements that we wish to weigh in here.

"When coming across the sentence 'The horse is connected with the waters', this seems to be an unintelligible statement as many of the equations referred to above. As far as I can see, no relevant noem, no important concept of our encyclopedic knowledge connects 'horse' with 'water'." Now, in essence, I do think that he has hit upon the right sensibility, as when he quotes: " "The gods love the hidden, the non-apparent" (parokṣapriyā hi devāḥ)" Yet I think he goes awry when he then considers this hiddenness to consist merely in the similarity of sounds. "aśva 'horse' is aśru 'tear' because they share, as in the earlier example of dakṣiṇā = dakṣiṇaḥ, a similarity in sound."

Of course, it may be that this "symphony" matters, in the sense of jāmi, i.e., the sounds being neither identical nor entirely different, but just "similar". Yet there are other elements that we wish to weigh in here.

Witzel recalls the following myth to connect the horse with Prajāpati:

"This still leaves the relationship of the horse and Prajāpati unaccounted for. The solution, once luckily found in the texts themselves, is a rather simple one: A myth is related: 'Prajāpati (the lord of creation) wept. His tear fell down. Out of this, the horse developed. It neighed. It let some dung fall down, turned around, and sniffed at it' (- a good observation of the boundary marking habits of horses). Probably, this story would be remembered by a Vedic Indian if he were to explain the relationship of the three sentences about the horse mentioned before. The myth unifies these statements: The horse is related to Prajāpati, it is of Prajāpati- nature (prājāpatya) because it developed from his tear; it is related to the waters as it was born from salty water, from Prajāpati's tear. As it happens, both 'horse' and 'tear' sound similar in Sanskrit: therefore the hidden, secret name of 'horse' can be 'tear'."

"This still leaves the relationship of the horse and Prajāpati unaccounted for. The solution, once luckily found in the texts themselves, is a rather simple one: A myth is related: 'Prajāpati (the lord of creation) wept. His tear fell down. Out of this, the horse developed. It neighed. It let some dung fall down, turned around, and sniffed at it' (- a good observation of the boundary marking habits of horses). Probably, this story would be remembered by a Vedic Indian if he were to explain the relationship of the three sentences about the horse mentioned before. The myth unifies these statements: The horse is related to Prajāpati, it is of Prajāpati- nature (prājāpatya) because it developed from his tear; it is related to the waters as it was born from salty water, from Prajāpati's tear. As it happens, both 'horse' and 'tear' sound similar in Sanskrit: therefore the hidden, secret name of 'horse' can be 'tear'."

Now, at this point, Witzel's explanation falls entirely to referring the meaning of one passage to another. And in this, we do find some sensibility. But we haven't discovered as yet anything which makes it feel compelling. I mean only to add this additional ingredient. Witzel himself admits that this explanation isn't really compelling but still appears as if a fabrication: "The problem is whether this explanation really answers the question posed by these three sentences. The myth which unifies them looks more like a fabrication in the fashion of the other varified tales about Prajāpati, which always come in handy as explanations, (cf. also H.-P. Schmidt 1979 p. 278). One could even suspect that the myth had been created because of the similarity of the two words denoting 'horse' and 'tear'." While Witzel leans on a rather phonological, noematic explanation, we have discovered an "missing link" of sorts, a hermeneutical cypher which signals the associations in more compelling terms. The problem again is that there is nothing very compelling about the noematic explanation; we, so far, don't feel that the Brāhmaṇas make any sense, even if they are apparently self-referential. It seems vaguely possible that Witzel's explanation is correct, but we simply don't have any motive that compels us to regard this as a good or plausible explanation. The phenomenality of the whole comparison seems more or less still lacking.

But in fact, there is one domain in which this connection drawn between a "horse" and "the waters" seems to us almost strikingly plausible. For this, we need only look to the ancient obsession with Uranography. In order to signal the somewhat idiomatic style with which the Ancient Vedic Brāhmaṇas undertook this practice, I coin the term, "Varuṇography," on the strength of Dumezile's Ouranos-Varuna essay. Among the earliest ontologies in the Vedas gives us the basic divisions of bhūḥ, bhuvas, and svar, or "Earth", "Atmosphere," and "Heaven". Sky, has been divided into two divisions, one seen during the day, one seen at night. Svar is "higher than" bhuvas, the atmosphere. And it is in the Svar, the heavens, that the devas, the divinities live. This alone already suggests that very many of the Vedic and Hindu deities (if not all of them) are directly associated with constellations. The work and method of determining these associations, I term as Varuṇology.

It needs to be underscored that the methods I employ are a little bit elusive to the "uninitiated". It will not always be obvious where best to start, not least, because every postulate I will make here relies in turn upon yet other postulates which are not immediately self-evident. It is rather in the coherence of these postulates that I find the strongest form of evidence for the overall truth. No postulate here will stand on its own ground, but in every case, must be seen in light of the other postulates. Each postulate, moreover, is but one of several competing postulates, so that the identity of a given "connection" (to use Witzel's language) is not to be taken as total or exhaustive of the possible identifications. That one constellation is identified in a particular way in one passage in no way prevents that same constellation from taking on a whole new identity, even sometimes within the same narrative. Sometimes, constellation may play two or more roles so that it will seem as if talking to itself! Hence, one finds that the rational process for securing the most plausible sensibility of the Brāhmaṇas' esoteric connections requires a bit of conceptual meandering, sometimes from one narrative to another, sometimes from one constellation to another, sometimes from one concept to another. We will, of necessity, short-cut some of this, and so, it may appear to our reader, for a time, that some of our putative postulates go inadequately substantiated. We beg the reader's patience in this regard, as we do have evidence which will become apparent in due course to those who are adequately familiar with Uranography, but which will require the reader to take up the study of these constellations as a crucial part of understanding the rationality of the "system".

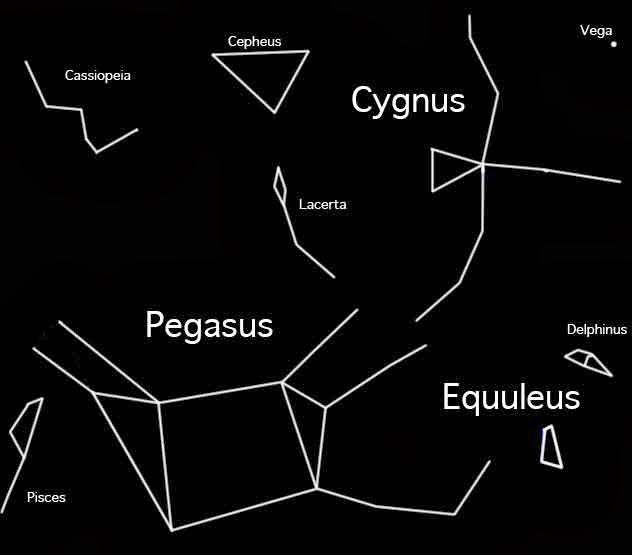

With that in mind, let us now turn to the constellations which, to my reading, provide us the most plausible lead for rendering sensible Witzel's own chosen example of "magical thinking" in the Vedas:

Of immediate significance are three constellations: Cygnus, Pegasus, and Equuleus. These three form a crucial trace of the original sense of this earstwise enigmatic passage from the Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa. Here we see that they are in close conjunction. Moreover, these three constellations rest in a portion of the sky known to antiquity as the "Deluge". We will not concern ourselves immediately with the original cause of such a name, but will only indicate the immediate symbolic sense of the term; this very large region of the sky is populated with constellations that are of an aquatic character. Among the "aquatic" constellations, there are, Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn, Cygnus, Delphinus, and others. The earliest historical origins of such identifications for these constellations are to myself still a mystery, but they do make clear one possible meaning of "the waters" in Witzel's example (note also that "Winter" is derived from an older term meaning the "Waters", given that the Sun inhabits this part of the sky during the Northern Winter). This becomes more evident when we note that Equuleus' head is "alligned" with two prominent stars in Cygnus. This alignment provides us with one possible sense of "tear", for if we take these two stars in Cygnus—namely, Sadr (Sindhi for "heart") and η (pronounced "eta") Cyg—as "eyes" of Prajāpati, then certainly there are two traceable lines which form the "sides" of the "tear" by falling in a straight line from these eyes.

Moreover, this image might suggest that Prajāpati gave birth to this Deluge with his own tears! We have elsewhere (forthcoming) made note of over 80 elements of convergence which collectively signal the identification of Prajāpati-Brahmā-deva with Cygnus. We will here mention just a few prominent indicators, which stand more well on their own, and so do not require further tracing to other postulates. For one, Brahmā is said to have a Swan vehicle (haṁsa). Another important signal, Brahmā is said to have four heads (catur-mukha) which correlates well with the four branches of Cygnus, generally drawn in a cross-like figure. Further, Cygnus is superimposed upon the core of the Milky Way Galaxy, suggesting its identification of the celestial Ganges, which is said to usher from Satya-loka, Brahmā's heavenly abode. The Astronomer, Raghava Rao, has also made this particular identification of the celestial Ganges. There are many other such postulates which further strengthen this single identification of Prajāpati-Brahmā with Cygnus, but many of them require delving into very complicated semiotic systems, so I will avoid entering further into that matter just at present.

There is another interesting connection to consider here, in relation to Pegasus. It is notable that Pegasus is "upside down", a strange formation which occasionally catches the attention of archeoastronomers (this same curiosity is found in the constellation of Hercules, for example). If this was the product of an inversion in prehistory, we might expect what is now taken to be Pegasus' front as rather his behind! And this would further strengthen our reading of the "horse-head = Prajāpati-tears = horse-dung = Equuleus" thesis. Let us recall the brief myth which Witzel relates: "Prajāpati (the lord of creation) wept. His tear fell down. Out of this, the horse developed. It neighed. It let some dung fall down, turned around, and sniffed at it' " Note that the horse defecates, and then turns around to sniff it! Here, we see the Brāhmaṇa attempting to describe how it is that the Horse is upside down! Thus, this upside-down horse, Pegasus, indeed is quite old!

Now, if I were to be required to proved the identity of any of these mythic elements, without drawing evidence from other mythic elements, I would be left with a much more difficult—nay, impossible, task. But we do see here, a sensible, compelling reading of these Brāhmaṇa passages relating the horse to the tears of a creator God, and to horse dung.

Indeed, I will go so far as to argue that astronomical information is very frequently embedded in the passages of the Brāhmaṇas. When these elements are all taken together and identified, we will find that the texts are not as obscure or difficult to interpret as they were previously. Simply by attending to the question of the domain we are to investigate, Svar, we know where to look for further phenomenal data. This has the potential to constitute a paradigm shift for interpreting the semiotics of the Brāhmaṇa texts. How much more is in these works which we have hitherto failed to recognize in its phenomenal originality, only because we lacked the right sort of hermeneutic sensitivity, and were unable to previously determine the primary domain of inquiry, i.e., comparative archeoastronomy?

A comparative archeoastronomy is thus greatly in need here. My research into this domain indicates that a treasure-trove of narrative tropes may be traced to astronomical—or rather, astrotheological—conversations held between various civilizations in hoary antiquity: elements which today survive in Chinese, Egyptian, Indian, Mesopotamian, Greek, Roman, and Norse astronomical narratives apparently pervade the Vedic works. Thus, close attention to comparative constructions can still greatly advance our collective awareness of the sense and meaning of the Vedic hymns, and may for the first time, hone the precision with which these hymns can be dated, using nothing more than semiotic evidence. In the end, this may prove one of the most precise ways to date the hymns of the Vedic Saṁhitās; if the ancient ṛṣis were being attentive to the general problem of describing the positions of the stars in the sky, perhaps they left us crucial clues to the historical origins of a calendar embodied in the sacrificial act. Did they acknowledge the ancient pole-stars? Which? With what hymns did they adorn them? Indeed, these being the "high-est" or "North-most" (ut-tama), can we say that the ancients, even prior to Hipparchus of Nicaea (c. 190BCE - 120 BCE), were able to understand the nature of axial precession? To determine this, we would need to be reasonably certain of the relationship drawn between the polestars and the yugas. And to do this, we would need to know the celestial who's-who of the Vedas. Here, we have managed to enhance the identification of Prajāpati with Cygnus, as well as Ucchaiḥśravas with Pegasus/Equuleus.

But this project ultimately rests upon the prior identification of hundreds of personas, objects, and narratives in the Vedic canon. Slowly, slowly, the Vedic world is resolving its identifications. Slowly, slowly, it is becoming evident why Viṣṇu, Brahmā, and Śiva "ascended" to the height of Monotheistic importance. Pandora's Box is opened, and there is no undoing what has become evident. What then can we say for the future of Astrotheology—to wit, the future of Hinduism? Time alone may tell.

But this project ultimately rests upon the prior identification of hundreds of personas, objects, and narratives in the Vedic canon. Slowly, slowly, the Vedic world is resolving its identifications. Slowly, slowly, it is becoming evident why Viṣṇu, Brahmā, and Śiva "ascended" to the height of Monotheistic importance. Pandora's Box is opened, and there is no undoing what has become evident. What then can we say for the future of Astrotheology—to wit, the future of Hinduism? Time alone may tell.

Bibliography:

Dumezile, Georges. Ouranos-Varuna: Essai de mythologie comparée indo-euroéene, 1932.

Kaufmann, Walter. From Shakespeare to Existentialism. Princeton University Press, 1980.

Pollack, Sheldon. Mīmāṁsā and the Problem of History in India, Journal of Oriental Studies, 1989.

Raghava Rao, Gobburi Venkatananda. Scripture of the Heavens, Potti Sree Ramulu Telugu University, 1997.

Smith, Brian K. Reflections on Resemblance, Ritual, and Religion. Oxford University Press, 1989.

Witzel, Michael. On Magical Thought in the Veda. 1979.

Author Unknown. Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I'd love to hear from you! Let me know your reactions to these blogs! Feedback helps improve the quality of the blog!